Bela Curcio didn’t ever expect to look like his dad. Curcio’s father—a burly Italian man from Queens, New York, with broad shoulders and a furry mustache—was “peak masculinity,” he says. Curcio, on the other hand, was a self-described awkward teenager who was only playing around with the popular photo-editing software FaceApp as a way to test the waters. In 2022, Curcio was on the fence about whether or not he wanted to begin his physical transition as a transgender man. Through a few filters and light editing, he was able to see himself actualized on the screen of his phone.

“It made me cry,” Curcio explains, admitting that the resemblance between him and his father was uncanny. The longer Curcio takes testosterone as a form of hormone replacement therapy in his medical transition, the more he thinks the resemblance grows between him and the male relatives in his family. “I was thinking, ‘This would be my reality if I had been born as his son.’ That just sent me into a spiral of, ‘Wow, I am his son,'” he says.

(Image credit: Courtesy of subject)

The photos Curcio took at the start of his transition are just the tip of the iceberg, he tells me. For Curcio and countless other transgender youth in America, a form of gender-affirming care is now in the palms of their hands with the availability of artificial intelligence–based filters and apps. At the press of a button, users can instantly toggle between presenting as male or female, with AI helping to enhance jawlines, add facial hair, soften cheeks, or lengthen hair. FaceApp, available on iOS and Android app stores, is one of the more common apps trans men and women use. As gender-affirming care continues to be overwhelmingly challenged in the United States, according to the Trans Legislation Tracker, it’s more important than ever to keep these tools up and running.

Since launching in 2017, the tech, along with most other AI-powered tools, has only gotten stronger. Users can now select what parts of their unfiltered faces they’d like to see altered. Curcio tells me he used the masking tool in lieu of the standard gender-swap filter because it’s more realistic: “I wanted to know what I would actually look like. The reality is I’m not a gym bro. I’m not a protein shake person or someone who’s trying to beef up. I’d rather look like Troye Sivan.”

(Image credit: Courtesy of subject)

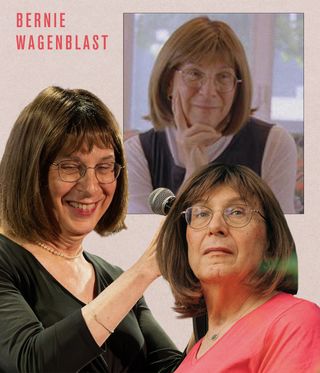

For some trans people, especially those transitioned later in life, FaceApp and other AI-powered gender-swap filters offer a glimpse into an alternative universe, one connecting how they feel inside with how they present to the world. In Bernie Wagenblast’s case, FaceApp was a pivotal tool in the early stages of her transition. Wagenblast, a radio journalist most well-known for being the voice behind the New York City subway announcement system, went viral in 2023 after coming out as trans at 66 years old. It’s never too late to live life authentically as yourself, she says.

In 2017, Wagenblast uploaded a selfie of herself on FaceApp after seeing a late-night-show comedy segment where a TV host ran photos of football quarterbacks through the gender-swap filter. Although she knew she was a woman her entire life, it was the first time she had seen herself realistically portrayed as one—long hair, rosy cheeks, and a swipe of AI lipstick across her after photo. Wagenblast uploaded the before-and-after photos on Facebook as a joke, but after reading a few affirming comments, she realized that perhaps there was more support for her than she thought. Slowly but surely, she began her medical and social transition, beginning on the lowest dose of estrogen and changing her legal name and driver’s license notation from male to female.

(Image credit: Courtesy of subject)

“In the meantime, I’d go back to FaceApp to see how they updated it and different changes they’d made. There were different hairstyles and makeup, so I would play around with that,” she says, referencing the slew of photos she’d save in the safety of her camera roll. Although Wagenblast knew she wouldn’t look exactly like her filtered photos, it was more than enough to calm her nerves.

For a long time, she was nervous about her transition. Would she like how she looked? Would she live up to the fantasies she had created for years about living as a woman? Would the world be kind? For Wagenblast, though, there’s been a freedom with abandoning the perceptions of other people. She tells me she’s never felt more comfortable and confident in her life. “My philosophy at this point is that I’m just going to enjoy this,” she says. “This is something that I’ve dreamed of all of my life that I’m finally getting to experience.”

(Image credit: Courtesy of subject)

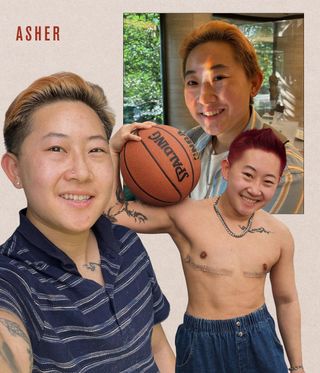

Asher Wang “cracked his egg” in one of the most Gen Z ways—TikTok, naturally. The 24-year-old went viral last year after uploading a gender-swapped before-and-after video using CapCut, a filtering and editing application. In it, Wang admits the AI-laced images are what got him to realize he was transgender. Open the comments and you’ll find a slew of people agreeing with the experience: “Saammme,” writes one. “Real,” says another.

On the day Wang first used the filter, he tells me he was feeling a heavy bout of gender dysphoria—the unease that occurs when your biological sex doesn’t line up with your gender identity. Although Wang didn’t have the words for it at the time, he knew something was wrong. “I just went home and, while my brain was on autopilot, looked up ‘gender swap’ on the App Store. I downloaded FaceApp, and I immediately felt better after running my photo through the filter,” Wang explains. At the time, Wang didn’t automatically assume the relief he felt from seeing himself as a man meant he was transgender. Rather, it affirmed his belief that he definitely wasn’t a woman. “I didn’t connect the dots until almost a year later when I realized, ‘Maybe I’m trans instead of being gender-fluid or nonbinary,'” he says.

(Image credit: Courtesy of subject)

Wang would end up going back to FaceApp throughout his early transition, each time growing closer and closer to deciding to begin medically and physically take steps to present as a male. With each filtered photo came another bout of reassurance that he was making the right choice, even if the filters weren’t as accurate as they could be. Like most AI-based programs and tools, most of the gender-swapping filters available to the mass market heavily rely on white, Eurocentric data input when showing users what they would look like as male or female. As a trans person of color, Wang says there’s quite a long way to go for the technology to be truly reflective.

“I remember when I was first using FaceApp. It spit out a photo of me with tons of facial hair. As someone with Asian genetics, I’ll probably never grow a beard or anything like that. I knew this app was clearly not made for me,” he admits. The app previously pulled racist AI-based filters that promoted digital yellowface and blackface, according to The Guardian. “It was something I struggled with in terms of representation. Most trans guys you see on social media, or media in general, are skinny white dudes. I didn’t want the only representation I had for myself,” he adds.

(Image credit: Courtesy of subject)

Throughout trans-centered spaces online, more and more trans people of color have begun to put a critical eye to the use of AI filtering tools as the end-all, be-all of gender-affirming digital representation. Not only are some filters inaccurate, but the pressure to succumb to beauty standards—especially the pressure to pass as a cisgender woman or man—is also at an all-time high.

For impressionable trans youth looking at FaceApp and other gender-swapping AI tools, it’s important to remember that, left unchecked, the app can present unrealistic expectations for what they would look like after starting hormone replacement therapy or other gender-affirming care methods. It’s important to recognize that facial filters and digital tools exist in context, Bridgette Jayne Grady, a 38-year-old gender-fluid TikTok creator, tells me. Although these can be life-saving tools, obsessing over minute details of how your post-transition photos would look may lead to even more gender dysphoria, especially for queer youth who may not be in supportive home environments.

“The novelty of being a teenager and seeing myself if I had these tools back then would have brought me so much relief and joy, but the novelty would have worn off fast.” Grady tells me, explaining the feeling that would have come with realizing their gender identity much earlier but not having access to gender-affirming care.

There are small ways to incorporate gender-affirming care into the lives of most trans men and women, Laura Lewman, ND, a Portland-based esthetic medicine specialist at SkinSpirit, tells me. Procedures like dermal fillers, laser hair removal, and Botox injections are more widely accessible and affordable than aesthetic procedures like facial feminization surgery and chest reconstruction surgery. Within an hour-long clinic visit, jawlines can be sharper, lips fuller, and facial hair less pronounced.

You’re trans enough if you’re not out to anyone. You’re trans enough if you don’t pass or don’t want to pass. You’re trans enough if you’re still exploring what being trans means to you.

Bridgette Jayne Grady

“One of the most important things about treating my trans patients is figuring out where people are at with their transition and how far they want to go,” Lewman explains. “There are so many options for these treatments that are relatively safe, generally less expensive, and can really make some meaningful changes for people.” It’s all about providing realistic, proper care that will leave her clients feeling like they truly see the best versions of themselves reflected in the mirror.

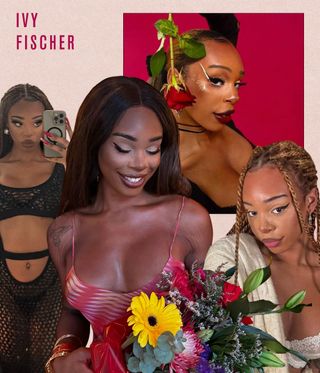

For years, Ivy Fischer, a 24-year-old dancer has been editing herself on the app ahead of doctor’s office visits and other aesthetic medicine consultations. It’s an easy way to visualize the way she wants to present to the world, she tells me. Although FaceTune and other editing tools are an incredible useful tool when Fischer first began her transition, it’s important to note the self-work in getting to a place of genuine appreciation and care for her body began years before. “[The apps] are instant gratification because you’re able to see yourself how you want to see yourself. But also, that’s not how it works in real life. It’s all in steps” she tells me. “The detriment to having such quick and fast access to FaceTune and all these filters is that I feel like younger trans people may not prioritize the process and the time that that goes into self-actualization. You need to love yourself, nurture yourself, and do the work to feel confident and happy.”

As a Black trans woman, Fischer and her trans sisters are most affected by racial and gender violence within the queer community. Protecting her Blackness was one of the most crucial aspects of her transition when she began in 2016. Since then, she’s gone under the knife both domestically and abroad. Fischer jokes that she’s a big fan of plastic surgery, but it was important for her to not look like a whole new person. “I love my Black features. I love Black femininity. I love a Black standard of beauty, and my goal, throughout any of my surgeries, is to maintain my Blackness above all else,” Fischer explains.

Just like Wang, Fischer knew AI filters weren’t going to be accurate. Most make your skin lighter, your nose smaller, and your cheekbones less pronounced—all akin to Eurocentric standards of beauty rather than people’s individual features. “The gender euphoria that comes from using these tools, though, doesn’t come from how you look in the end. Rather, [it’s] the fact that you can envision yourself finally living as who you feel inside,” Fischer says.

(Image credit: Courtesy of subject)

Social media has outgrown the sparkly flower crown filters and dog emoji overlays that dominated our screens back in Snapchat’s heyday. Most cisgender people associate FaceApp and Facetune with a slew of cringeworthy celebrity editing fails, but for trans men and women, the apps are a lifeline. Like most things on social media, it’s important to be cognizant of what you’re taking in, Fischer tells me. You probably won’t look like a snatched, glowing doll if you’ve only been taking estrogen for six months, but with time and patience, you’re going to look back at your before shots in awe.

My philosophy at this point is that I’m just going to enjoy this. This is something that I’ve dreamed of all of my life that I’m finally getting to experience.

Bernie Wagenblast

When I ask Wagenblast if she ever looks at her old FaceApp photos, her voice tinges with emotion. She admits she doesn’t look at them as often since transitioning because she would previously seek out the images as a form of solace. Now, though, Wagenblast looks back on her old pictures with pride—they’re a reminder that she made it through. “When I created those, I thought that transitioning was not going to be possible for me, that it would just be something I would continue to have to fantasize about for the rest of my life, and that I would never get to experience it,” she says. “Now, I can look back on those photos and sort of say, ‘Huh, you did pretty well for yourself. You did get to do what you had always dreamed of, and now, you are living that life that you wanted to live.'”

:quality(70):extract_cover():upscale():fill(ffffff)/2025/01/30/866/n/1922564/5de1da7d679bd74385a671.79574530_Screenshot_2.png)